‘Forever chemicals’ contaminate more dolphins and whales than we thought – new research

Nowhere in the ocean is now left untouched by a type of “forever chemicals” called “per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances”, known simply as PFAS

Nowhere in the ocean is now left untouched by a type of “forever chemicals” called “per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances”, known simply as PFAS.

Our new research shows PFAS contaminate a far wider range of whales and dolphins than previously thought, including deep-diving species that live well beyond areas of human activity.

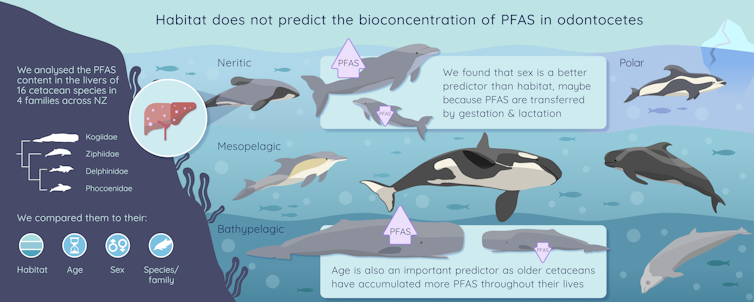

But most surprising of all, where an animal lives does not predict its exposure. Instead, sex and age are stronger predictors of how much of these pollutants a whale or dolphin accumulates in its body.

This means chemical pollution is more persistent and entrenched in ocean food webs than we realised, affecting everything from endangered coastal Māui dolphins to deep-diving beaked and sperm whales.

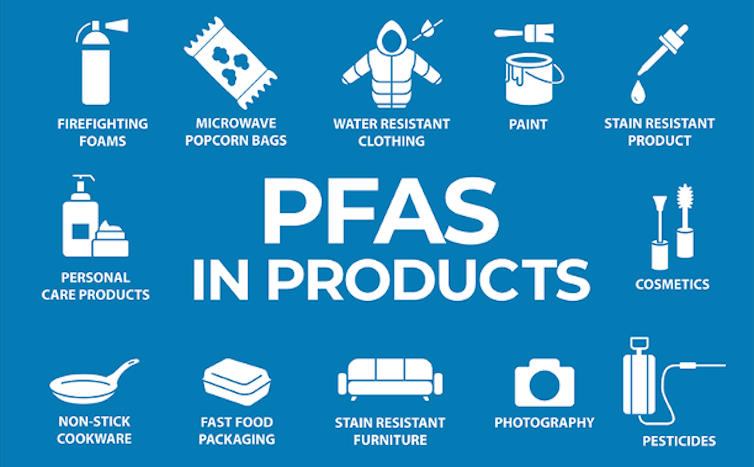

PFAS were originally designed to make everyday products more convenient, but they have ultimately become a widespread environmental and public health concern.

Our work provides stark evidence that no part of the ocean is now beyond the reach of human pollution.

What are PFAS, and why are they a problem?

PFAS are a group of more than 14,000 synthetic chemicals that have been used since the 1950s in a wide range of everyday products. This includes non-stick cookware, food packaging, cleaning products, waterproof clothing, firefighting foams and even cosmetics.

They’re known as forever chemicals because they don’t break down naturally.

Instead, they travel through air and water, eventually reaching their final destination: the ocean. There, PFAS percolate through seawater and sediments and enter the food web, taken up by animals through their diet.

Once inside an animal, PFAS can attach to proteins and accumulate in the blood and organs such as the liver, where they can disrupt hormones, immune function and reproduction.

Like humans, whales and dolphins sit high in the food web, which makes them especially vulnerable to building up these pollutants over their lifetime.

Whales and dolphins are the ocean’s canaries

Marine mammals are an early warning system of the ocean. Because they are large predators with long lifespans, their health reflects what’s happening in the wider ecosystem, including risks that can affect people, too.

This idea is at the heart of the OneHealth concept, which links environmental, animal and human health.

New Zealand is one of the best places in the world to study human impacts in a OneHealth framework. More than half of the world’s toothed whales and dolphins (odontocetes) occur here, making Aotearoa a rare hotspot for marine mammals and an ideal place to assess how deeply PFAS have entered ocean food webs.

We analysed liver samples from 127 stranded whales and dolphins, covering 16 species across four families, from coastal bottlenose dolphins to deep-diving beaked whales.

For eight of these species, including Hector’s dolphins and three beaked whale species, this was the first time PFAS had ever been measured globally.

We expected coastal species living closer to pollution sources to show the highest contamination, with deep-ocean species being much less exposed.

However, our results told a different story. Habitat played only a minor role in predicting PFAS levels. Some deep-diving species had PFAS concentrations comparable to (or even higher than) coastal animals.

It turns out biology matters more than habitat. Older, larger animals had higher PFAS levels, indicating they accumulate these chemicals over time.

Males also tended to have higher burdens than females, consistent with mothers transferring PFAS to their calves during pregnancy and lactation. These patterns were consistent across all major types of PFAS chemicals.

Why this matters

Our findings show PFAS contamination has now entered every layer of the marine food web, affecting everything from nearshore dolphins to deep-diving predators.

While diet is a major exposure pathway, animals could also be absorbing PFAS through other mechanisms, including potentially their skin. PFAS may further interact with other stressors, including climate change, shifting prey availability and disease, adding further pressure to species already under threat.

Knowing that PFAS are present across different habitats and species raises urgent questions about their health impacts. Are these chemicals already affecting populations? Could PFAS contamination weaken immunity and increase disease risk in vulnerable species, such as Māui dolphins?

Understanding how PFAS exposure affects reproduction, immunity and resilience to environmental pressures is now central to predicting whether species already under threat can withstand accelerating environmental change.

Even the most remote whales carry high PFAS loads and we know humans are not isolated from these contaminations either. Answering these questions is not optional but essential if we want to protect both marine wildlife and the oceans we all depend on.

The research was a trans-Tasman collaboration which also included Gabriel Machovsky at Massey University, Louis Tremblay at the Bioeconomy Science Institute and Shan Yi at the University of Auckland.![]()

Karen A Stockin, Professor of Marine Ecology, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa – Massey University; Emma Betty, Research Officer in Cetacean Ecology, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa – Massey University; Frédérik Saltré, Senior lecturer in Ecology and Biogeography, University of Technology Sydney; Australian Museum, and Katharina J. Peters, Lecturer in Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.