Of droughts and flooding rains

This time last year, I had just written an article on bushfire-resilient design in response to the Black Summer. Many of those who lost their homes from those devastating bushfires are still yet to rebuild. We (architects) are assisting many of...

This time last year, I had just written an article on bushfire-resilient design in response to the Black Summer. Many of those who lost their homes from those devastating bushfires are still yet to rebuild. We (architects) are assisting many of those who lost their homes through the archi-assist program set up by the Australian Institute of Architects. (If you know anyone who could do with some pro-bono assistance, please send them to www.archiassist.com.au.)

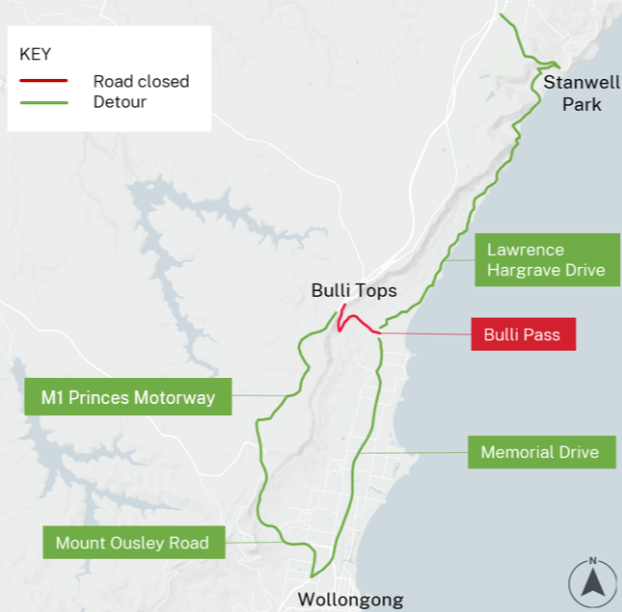

How long ago that seems! Both in time and weather events. Some areas of NSW have already received over a metre of rainfall in March! So, it’s time to look at flood-resilient design.

1. Location

Where you build a home makes a big difference. Thanks to advanced computer modelling tools, we can identify areas at risk of flooding during extreme rain events. However, some may think that building higher is safer and, whilst that might be true for potential water inundation, that’s not so the case for land slippage. There is mounting evidence to suggest that many areas of the escarpment are unstable to due the dynamic nature of the geology and hydrology of the area (not to mention the odd coal mine shaft underneath). Generally, the key to safe foundations in these locations is bedrock.

2. Building Form

The classic Queenslander is an example of a building typology adapted to our wet and dry cycles. These little beauties are also great for when it’s a super-hot day. You can go down under the verandah and it can be 10°C cooler, not to mention it’s a perfect place to keep the beer fridge, until it floods, that is!

But what about uphill where land slippage is more of a danger? This is where flood resilience and bushfire resilience aren’t looking after each other. Where a sheltered gully might offer better protection from a bushfire, it’s certainly not the place you want to be in a flood. Ridgelines are going to be a better bet and particularly if we can find our friend bedrock to sink our footings into.

3. Materials

I grew up in Brisbane, not far from a sports oval, which was not far from a local creek. As a result of heavy rainfall, one of the local stormwater drains became blocked and the bottom of our house became a mini Venice, and, no, we didn’t live in a Queenslander. The entire bottom half of the house needed to be gutted and rebuilt internally. Soggy insulation, timber floorboards and plasterboard were all carted off to the tip – only to be replaced by the same materials!

New building codes require building below flood levels to use certain types of flood-resistant materials that make cleaning up after a flood a little less messy and mouldy. Essentially, any materials that can soak up water are out (think wood and plasterboard) and those that can resist the effects of water inundation or when dried out keep their form are in (think steel, concrete and brick).

Also materials with inherent resilience to the impacts of bushfire.

Beyond the above three pointers, there’s also the obvious good roofing and drainage, landscaping away from the house, building down the gradient for steep sites eg. split levels, less reliance on retaining walls the better. An apron of paving or gravel around the perimeter can also help resist against localised flooding.

The CSIRO has published a great pamphlet called Foundation Maintenance and Footing Performance – A Homeowner’s Guide.

And, if you’re worried your house might slip down the hill, go to https://landsliderisk.org/resources/guidelines/