Science vs architecture

Some would say architecture is the perfect vehicle to bring together the arts and science. It was one of the main reasons I was drawn to the field. With the exception of sculpture or installation art, there aren’t too many other arts that need to...

Some would say architecture is the perfect vehicle to bring together the arts and science. It was one of the main reasons I was drawn to the field. With the exception of sculpture or installation art, there aren’t too many other arts that need to grapple with a number of scientific principles. That’s not to say art can’t grapple with all of the science that architecture does, but it doesn’t have to.

Architecture, on the other hand, hasn’t got a choice. It has to resist gravity, heat and cold, the effects of sun, wind and rain, as well as forming somewhat of a vessel for modern domestic living. The technology making its way into modern houses is diverse and can be truly high tech. Urban legend has it that Bill Gates’ home is so high tech, you rarely need to touch a surface except the floor!

Many architects would claim there’s always a tussle between the science side and the art side of architecture, but most, if not all, architects would agree that the best buildings harmonise the two, such that the art becomes a science and there’s a science to the art. Whilst there’s the obvious physics side of architecture that requires a building to stand upright and resist various forces, this has evolved to a point where almost anything can happen – think of the Burj in Dubai. Thanks to super computers and super materials, this area of the science of architecture is well practiced. What makes up the vast majority of the Architectural Sciences these days is all in the envelope. On a warming planet and with increasing energy prices, new buildings are seeking better eco-credentials so they can reduce their impact on the environment as well as their power bills.

Many traditional forms of architecture evolved around their genius loci, think igloos, pueblos, the longhouses of Asia and, in more modern times, the “Queenslander”. Through many years of evolution, these traditional forms were developed to respond best to the local environment and with the available materials at hand. From industrialisation onward, much of modern architecture forgot these traditional forms as they were seen as antiquated. Why build like that when we have modern materials, easy access to energy and water etc. Oh, what fallacies we pursued! These forms are now taking on new interest and being reinterpreted in the modern era but it takes a long time. One visit to a recent “homeworld” subdivision will show that we are still unlearning from our industrialised past.

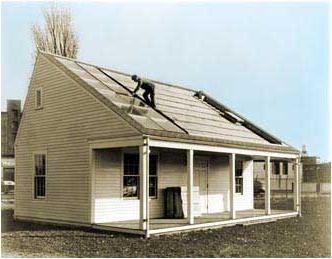

A little research into the history of passive designed, so-called ‘low energy’ houses, and the earliest one I could find was a little house called ‘Solar 1’, designed and built in 1939 by MIT in USA. (Check it out at http://web.mit.edu/solardecathlon/solar1.html.) It looks just like a normal weatherboard cottage with some sort of early version of solar panels on the roof. Even more fascinating, and 50 years earlier, was the construction of the ‘Fram’ in 1883. Possibly the first passive designed construction was actually a boat! Designed by naval architect Colin Archer and built to withstand the extreme conditions of Arctic exploration, it was air-tight and had thick insulated walls, triple panel windows, and controlled ventilation. One day (I write this during the hard lockdown of July 2021) you might be able to go and see it at Norway’s Bygdøy Museum.

The evolution of passive designed houses has evolved markedly since then. It wasn’t until the ’70s when the first generation of solar panels were starting to improve and become slightly affordable that we started to see the integration between architecture and solar capture. These days houses can achieve net zero energy and better. One of my favourites is the 10-star home by Clare Cousins Architects. This house is carbon positive, meaning that during its lifetime it will negate its initial carbon footprint to build. Built in 2017, even a lot of its technologies are out of date but the owners benefit from their initial insight and careful design. It forms part of a community subdivision in Southern Victoria where they mandate a minimum 7.5 star NatHERS (Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme) rating for every new build. Now if only more subdivisions saw some art and science coming together in passive harmony…