Social licence might be coalmine's biggest hurdle

On a trail run in the Royal National Park after heavy rain, Russell saw inky water and black rocks littering the sandy banks of the Hacking River. He knew what he’d found

Public trust is easy to lose, as Russell Arnold’s story shows, and the fallout can trickle through the years until it becomes a deep well of disillusion with the institutions of democracy.

Like the environmentally minded people at Protect Our Water Alliance (POWA), Russell opposes Peabody’s application to expand coalmining further under the Woronora water catchment via longwalls 317 and 318. The application process is happening now, with a decision expected in coming months, but for this nature-loving bricklayer, the roots to his opposition run deep in the past.

Russell grew up in 1980s Helensburgh on Old Farm Road, a street that backs onto bushland shielding the historic Metropolitan Colliery from suburbia. For an imaginative boy accompanied by his dog, walking in the forest, crossing creeks and looking for animals was the foundation for a lifelong love of nature.

“I’d spend whole weekends just wandering through the bush, marvelling at it,” says Russell, who came to know the area like his backyard.

So when, decades later, Russell was in his 40s and on a trail run in the Royal National Park after heavy rain, he saw inky water and black rocks littering the sandy banks of the Hacking River, he knew what he’d found.

“I was running along Lady Carrington Drive, and I just saw the coal all through the Hacking River,” Russell says. “I was just absolutely amazed that that was allowed to happen in a national park.

“I was really angry and upset.”

He says he tried to sound the alarm with the ABC and the NSW Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), but nothing happened. Russell didn’t contact the US mining company, seeing it as “a futile gesture, considering their record”.

“I wrote to the EPA,” he says, claiming these reports were met with “disregard” and he was told it was “naturally occurring” and “old” coal.

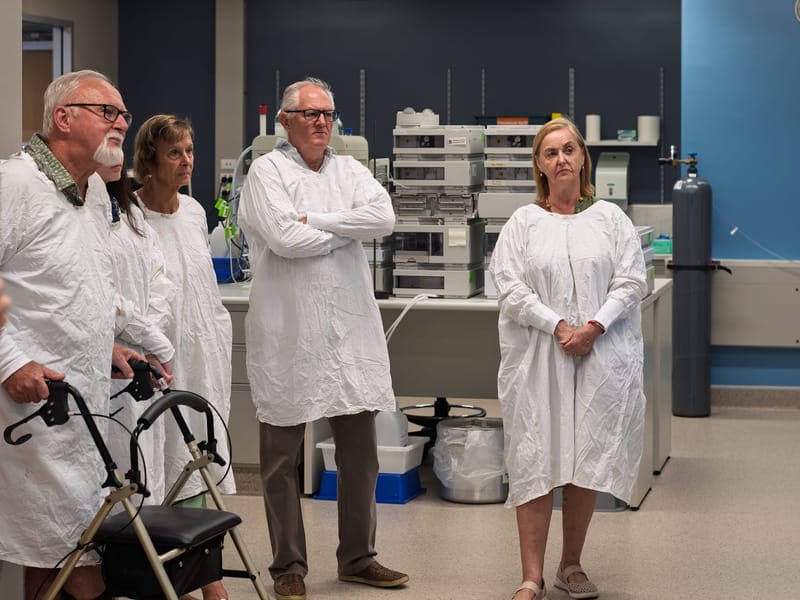

Bricklayer Russell Arnold. Photo: Anthony Warry

Russell has worked most of his life in construction and is currently a bricklayer, but in his 20s he studied art and media at university. So he set to work, filming his finds, creating a YouTube channel and self-publishing the clips.

“I was like, ‘No, I've grown up here my whole life. I know what's old and new, I've seen the river through countless years.' And that's when they started getting a bit worried.”

Months later, in September 2022, another local trail runner, Wild magazine editor James McCormack, found coal waste in Camp Gully Creek, which flows through Helensburgh and into the Royal National Park and the Hacking River.

This time the TV cameras rolled in and the scandal led to the EPA prosecuting Peabody’s Metropolitan Collieries in the NSW Land and Environment Court over its failure to maintain a dam that overflowed with coal-laden water.

In March 2025, the EPA announced that fines and fees totalled more than half a million dollars. Even in Helensburgh, where coal has been extracted since the 1880s and the mine still employs 400 people, public trust took a knock.

Wild magazine editor James McCormack. Photo: Anthony Warry

Transparency will be vital to Peabody regaining a social licence, but the media are not permitted at its community consultative committee meetings, and the Illawarra Flame understands that Metropolitan’s current CCC president is unlikely to grant interviews afterwards, leaving us with only publicly available minutes.

Insights are limited, including on two applications to be assessed this year. On longwalls 317-318 modification, the most recent minutes, from November 2025, reveal little more than that responses are on the Department of Planning’s website and “225 submissions were made, with 34% in support”. On Exploration Lease Area 6929, further west into the drinking water catchment, the minutes say: "This would be by inseam drilling, with no disturbance of the surface."

Russell told the Flame he felt “massively” let down by the government and its regulatory structures.

His experience with the EPA led to him connecting with activists at Sutherland Shire Environment Centre, then led by Dr Catherine Reynolds, who in 2019 started a petition calling for an end to longwall coalmining in the Woronora Special Area that was signed by more than 10,000 people.

A new petition she started late last year to counter the latest threats has more than 1200 signatures, including Rising Up documentary maker Kal Glanznig, the youngest independent councillor in the Sutherland Shire.

Environmental activist Dr Catherine Reynolds. Photo: Anthony Warry

“Mainly because I grew up around this area, I love the environment,” Russell says. “I'm currently studying conservation and ecosystem management diploma, and hope to get into the National Parks Service.”

In particular, he is passionate about protecting birds, such the powerful owl. This apex predator is Australia’s largest owl and one of several endangered species that thrive in the Woronora Special Area, where Peabody’s State Significant Development (SSD) application is located.

This SSD, labelled as a “modification” to the original 2009 approval, is to extend an existing longwall, add a new one, dig a ventilation shaft and build a new access road west of Helensburgh’s Metropolitan Mine.

“It always seems to be the interests of big business over anyone else,” says Russell. “The planet's crying out for something different instead of just more of the same.

“I'm very disillusioned by the whole concept of political action. You see it in a lot of democracies around the world, obviously, with America, but even the UK. I think people have sort of lost faith in the democratic process, which is sad.”

Even the response from the Independent Expert Scientific Committee on Unconventional Gas Development and Large Coal Mining Development (IESC) – published in November and flagging “irreversible changes" to fauna, flora and ecological processes in coastal upland swamps – does not reassure Russell.

“I'm sure it's all been 'properly' checked and an environmental survey conducted to tick all the 'right' boxes to allow the mine’s continuance, as this coal is of the highest quality, and they want it. But gee, it makes me uneasy and sad reading that.

“I find the report shows that damage to the environment is guaranteed. Yet still leaves the door open for the decision maker to proceed.”

If it does, the “modification” will demand greater than ever public trust in both the mine and its watchdogs. No trail runners are likely to stumble on black sludge in a special area where even bushwalkers are forbidden and trespassing penalties may be up to $44,000.

EPA responds

In February 2026, the NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) acknowledged Russell Arnold’s accounts was among community reports that drove its 2022 investigations. An EPA spokesperson highlighted the difference between fine coal and legacy coal, which the Illawarra Flame understands would require major works to remove, disturbing the riverbed and vegetation.

“Camp Gully Creek and the Hacking River contain some ‘legacy coal’, which is typically larger pieces (>5 cms) and well rounded by abrasion from an extended time in the river,” the EPA spokesperson said in a statement.

“This coal was most likely deposited in the river during the early operation of the mine in the 1880s, when there were few environmental controls or legislation to prevent it. This legacy coal is distinct from the fine coal material that came from the Metropolitan Collieries’ site in 2022.

“In August 2022, the EPA varied Metropolitan Collieries’ licence, requiring clean-up of fine coal in Camp Gully Creek and an expert assessment of the possible environmental impacts. This was in response to community reports of pollution, such as Mr Arnold’s, and EPA investigations.

“Following a major spill in September 2022 we prosecuted the company and ordered the removal of all coal material from both sedimentation dams by December 2022. Since that time there have been no significant pollution incidents from the colliery premises.

“Metropolitan Collieries’ licence now requires contemporary operational practices and real time monitoring of the sedimentation dams … Additionally, we continue to require further improvements to water management on-site and groundwater discharges through other licence conditions."

How the public can report pollution

Contact the EPA's 24/7 Environment Line – info@epa.nsw.gov.au or 131 555. "Timely reports with photos and specific locations are most useful," the EPA spokesperson said.