Friends plot to bring bursts of life to a place of rest

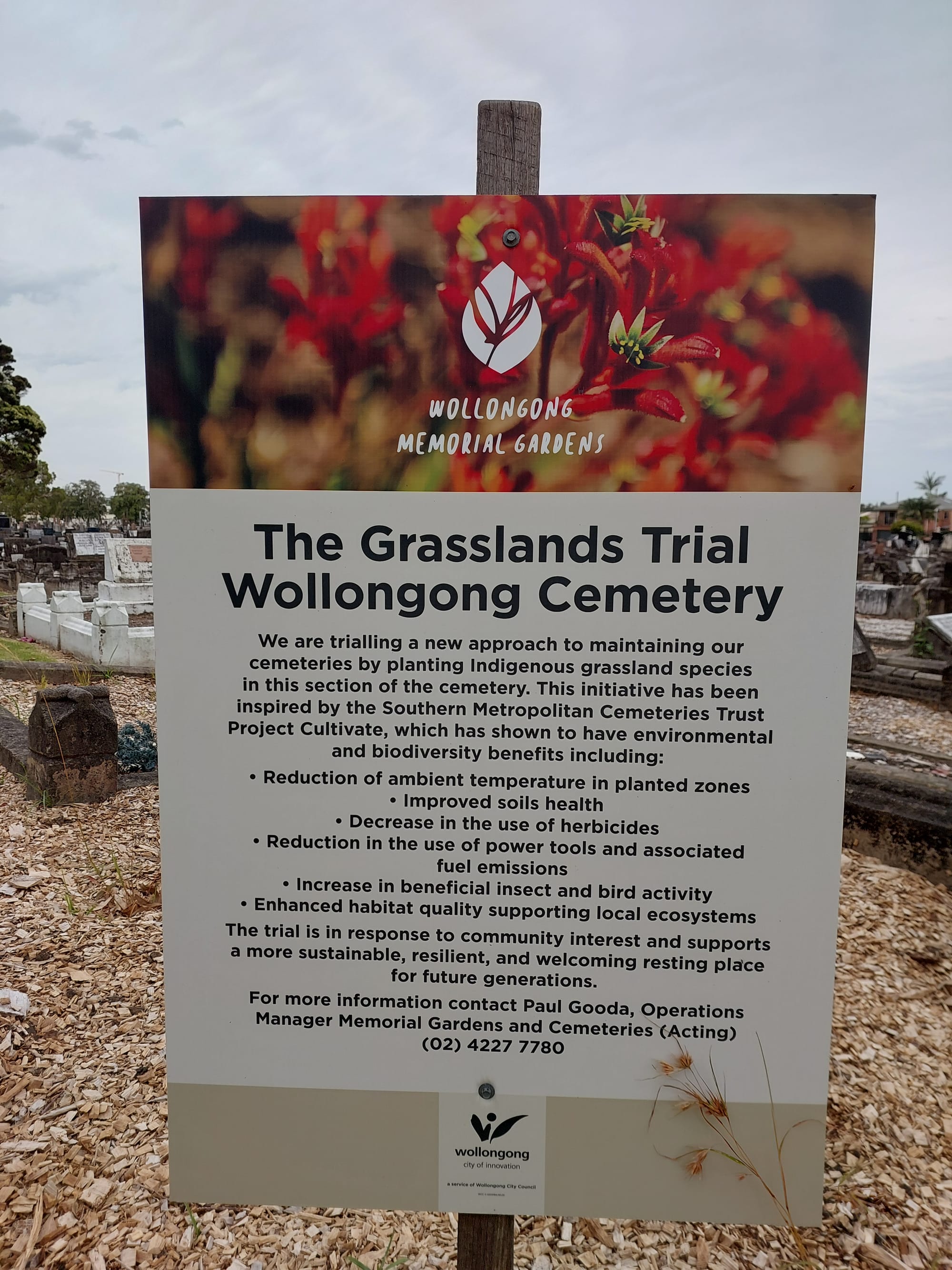

A volunteer-led grassland planting trial is softening curves, bringing people together and aiding nature within Wollongong Cemetery.

By Kathryn Morgan, student, educator and designer with Understorey Landscape Architects

There are just two rules: plant only local grassy woodland species, and stay inside the circle.

That’s the invitation of the Friends’ Plot, a volunteer-led grassland planting trial within Wollongong Cemetery. If you’ve walked through recently, you might have noticed a few patches of young grasses and groundcovers, earthen paths, with small logs and branches framing the beds.

The Friends’ Plot sits alongside Wollongong Council’s own native grassland trial. Together, these companion trials are exploring how parts of the cemetery might gradually shift from mown lawn to more climate-resilient, biodiverse management, which will complement remembrance, access and care.

Cemeteries are often overlooked as ecological assets, but in cities around the world, they hold some of the largest continuous areas of open ground, established tree canopy, and relatively undisturbed soils.

In a warming city like Wollongong, these qualities are significant. They offer opportunities for cooling, habitat and quieter forms of public use. The grassland trial asks a simple but important question: how might cemetery landscapes support both remembrance and ongoing life?

Emma Rooksby of Growing Illawarra Natives demonstrates how best to plant tubestock. At right: A bucket of plastic flowers picked up before planting at the Friends Plot, Wollongong Cemetery. Photos: Billie Acosta, 2025

Council’s plot focuses on establishing native grasses with maintained lawn paths between them. The soil preparation has been extensive and thoughtful, giving plants a strong start.

The Friends’ Plot took a different approach, with minimal ground preparation. Plants have been installed by hand into shallow augered holes no deeper than 20cm, with no imported soil. Fallen branches and sticks are gathered to define paths and protect young plants.

A small amount of organic fertiliser (mostly seaweed-based) was used very carefully at the roots to help the plants settle in, locally sourced mulch was applied, and the plot has been watered by hand.

The project is simple, low-cost, low-tech and designed to be cared for over time by people, and by the birds and insects we delight in seeing moving in.

Working bees bring together neighbours, artists, bush regenerators, children and university students. There’s a lovely sense of shared investment and care.

Jerrinja/Yuin artist and educator Peter Hewit opened the project with a smoking ceremony, and yarning circles with indigenous, settler and migrant participants have helped frame the Friends’ Plot as an exercise in care for a little piece of precious Dharawal Country.

I’m writing about the trial as part of my university research, and I’ve come to appreciate the way the volunteer and Council approaches are evolving side by side. This “both-and” model of institutional trial and community experiment allows different methods to be observed and compared over time.

But we also see a fertile space emerging for dialogue about maintenance, aesthetics, access, long-term care, remembrance, caring for Country and the many cultural nuances of how communities feel about end-of-life infrastructures.

Typical maintenance involves mowing and herbicides, which exhaust and deplete the landscape. Photo: K. Morgan, 2025. At right: Janine uses a drill auger to create holes just big enough for tube stock. Photo: Billie Acosta, 2025

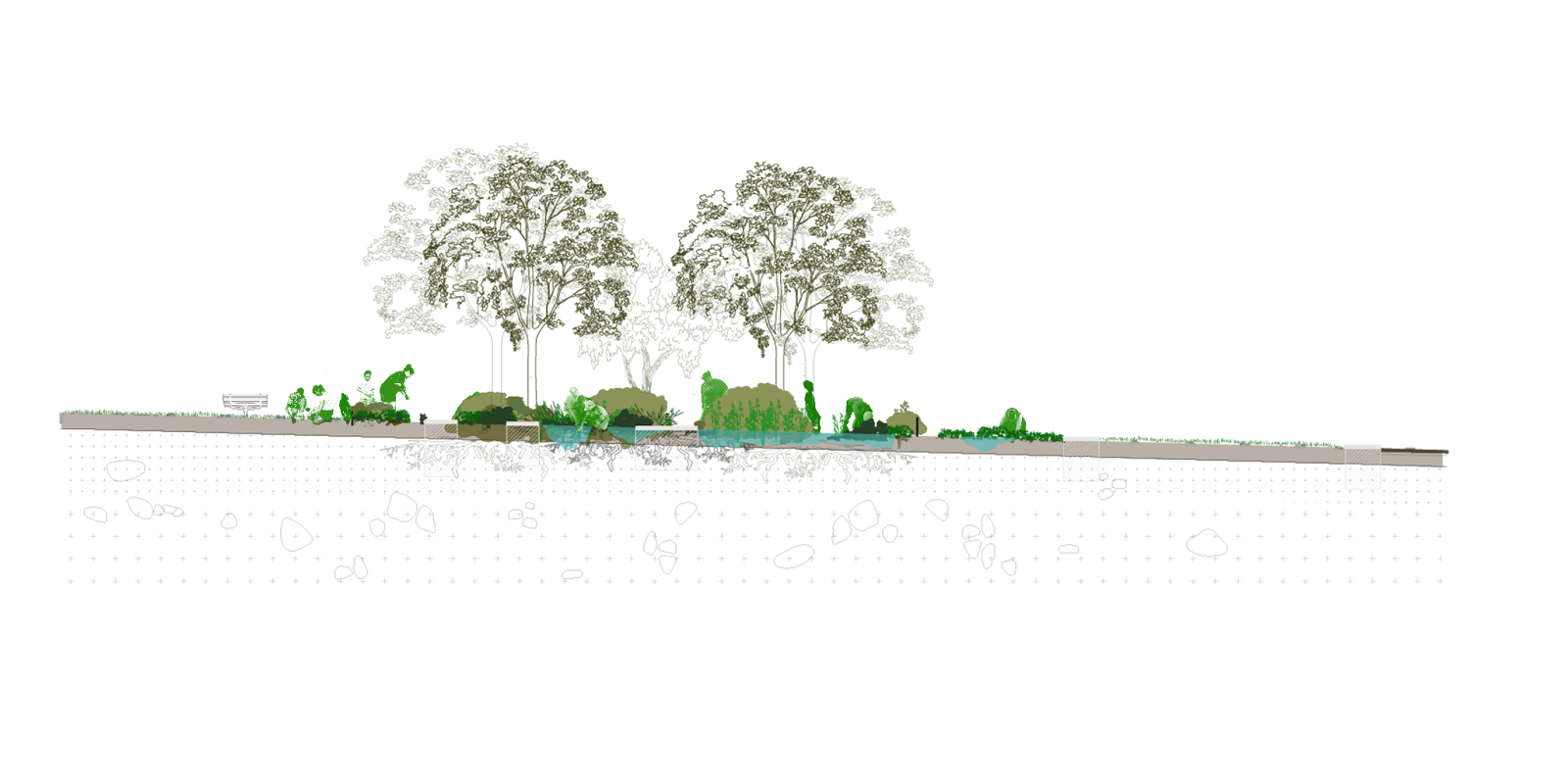

I've been working with some other landscape architects to think about Wollongong’s open spaces in the future. Graduate landscape architects Shirelle Altona, Isabel Peng and Louis Parsons-O’Malley were drawn to the cemetery trial as a way to engage with, in Shirelle’s words, “important conversations on life, death and how we grapple with and honour both in landscape, simultaneously, across cultures and time”.

Louis says “being involved in this project is bringing home the potential of cemeteries to perform multiple functions – being places for reflection, habitat, community and heat mitigation. I think we are going to find that multi-use spaces are vital in providing solutions to the problems that growing urban centres like Wollongong will face in decades to come.”

We know that real landscapes refuse to behave like drawings. Gardens are always in flux, bursting with their desire to grow, to bloom, ripen, drop seed, wither and succeed to new forms and lives and progeny. That aliveness is the pleasure of working with living systems.

The Friends’ Plot embraces the unpredictability that pictures and computer screens can’t convey, allowing a garden to emerge through time, shaped by ecology and the varied hands and intentions of those who come to care for it.

Walking in our cemeteries with local people has become an important part of my research. I’ve spent time with artist Michele Elliot, whose practice engages deeply with end-of-life care. Michele runs shroud-making and textile workshops for the community, approaching death as a process of transformation rather than closure.

“Cemeteries are complex,” Michele says. “They hold bodies and ashes – these soft materials – but the physical structures are so rigid.”

I've been surprised by the scope of interest people have – from microbes to poetry and walking – that stem from the unique public spaces that are cemeteries. I was surprised recently walking in the cemetery with conservation biologist Dr Beth Mott, a passionate advocate of grassy woodlands, when she expressed – dreamily, wistfully – her love of wild, rambling roses.

“What I really love about roses in cemeteries is that they are a flower that connects people across time and geography. If we use them wisely, exotics can make hardy habitat when we are starting to rebuild biodiversity, as places for wildlife to shelter and eat, and pioneers for sometimes more temperamental natives to follow. In cemeteries, an iconic flower woven amongst a native background can invite people to slow down and notice the beauty in all plants," says Beth.

It has also been touching to talk with Wollongong Council landscape workers who are so committed to beautiful maintenance of the place, which they know enhances the experience of grieving visitors. Some First Nations Friends Plot volunteers have talked about feeling a strong connection to Country, such as the way the paperbark trees shade us as we work and frame Grandmother Djeera – Mt Keira – in the distance.

Municipal cemeteries are typically designed and managed as formal gardens. That order makes sense: people need to find specific sites, honour specific individuals, and grieve in ways that feel contained and respectful. The grassland trial seeks to enhance that function but add just a touch of roughness to the smoothness – a curved line, a moist divot. How might a more complex, biodiverse landscape inspire different movement through the cemetery – perhaps offering a route that is not straight and efficient but meandering, with a high chance of meeting a bird, or having to pause, and marvel at flowers, or a family of butterflies?

As climate pressures intensify and burial culture shifts, cemeteries across NSW are being reconsidered as multifunctional landscapes. The Wollongong Cemetery grassland trial, including the Friends’ Plot, offers a local example of how this shift might begin, not with a master-plan, but with thoughtful, hands-on making, cooperation and time.

The Friends’ Plot will continue to evolve over coming months. Like the grasslands themselves, this is an experiment in working with multiplicity – of species, of people, of ways of talking about and being with land.

Have a look at some global and Australian precedents of cemeteries that embrace biodiversity. Volunteer and artist Penny Sadubin tells me of her time living near a “wild” cemetery – Abney Park, in London. “The abandoned chapel at the centre had long been a magnet for local kids, wannabe goths, art students, people making band videos – when we last visited, the chapel had finally been restored and reopened for ceremonies and concerts. A forest school and community garden run within the cemetery. Dog walkers and all of the above and more still pass through.”

If you’d like to join us, we’d love to hear from you!

Gardening at Waverley Cemetery, Second Nature Waverly. At right, World Landscape Architecture Forest path ecological garden at The Roques Blanques Metropolitan Cemetery, Barcelona. Photo: Jordi Surroca

Abney Park, London. At right: a sign for the Grasslands Trial at Wollongong Cemetery