Walking with trees: UOW’s revitalised Tree Walk invites connection to Country

Kathryn Morgan, a designer, educator and co-director of Understorey Landscape Architects, reports on the launch of the University of Wollongong's revitalised Campus Tree Walk

By Kathryn Morgan, an educator and landscape architect at Understorey

On a hot, dry morning on Dharawal Country, beneath the vast shade of a Moreton Bay fig, the University of Wollongong relaunched its Campus Tree Walk.

This is an expanded, collaborative project honouring 50 culturally significant trees. The trees were working hard for us humans gathered in the shade: cooling the air, softening the light, and offering their quiet, curvaceous infrastructure.

But as Associate Professor Anthony McKnight explained, they do more than serve us. They are our teachers. They are vital members of our community, and they deserve reciprocity. In the branches above us could be seen a sulphur-crested cockatoo, a peewee, a rainbow lorikeet and a noisy miner.

The launch unfolded as a conversation between many collaborators dedicated to the campus and its trees. Biologist Dr Alison Haynes reflected on the key attribute of the project – collaboration. “We walked the campus together, took our time to really look at the trees.”

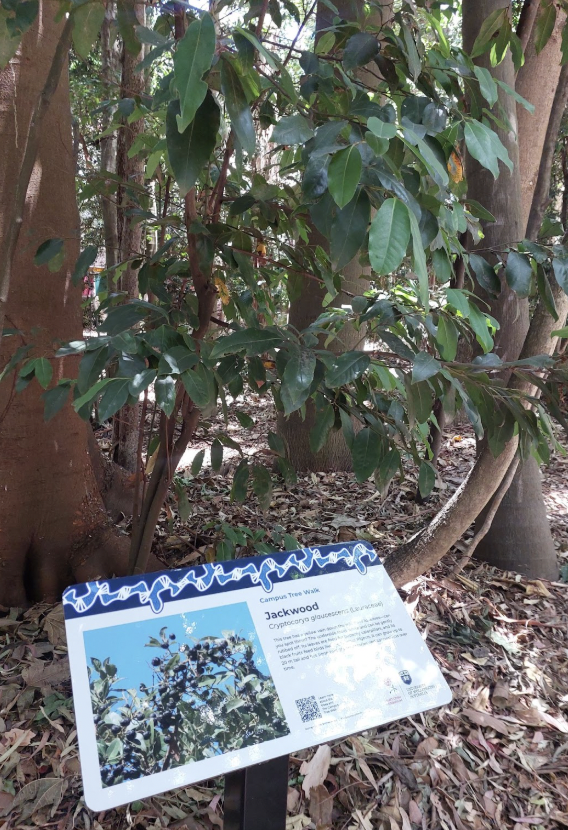

It was this slow, collaborative way of working that shaped the project and its cross-team collaboration. Landscape supervisor Mark Haining described the process as “relaxed but focused”. Even the challenge of reducing each sign down to 60 words was a collective effort, with local plant experts Emma Rooksby from Growing Illawarra Natives and herbarium curator Patsy Nagle crafting the captions.

Pictured left: Dr Alison Haynes talks about the role of collaboration in UOW’s revised Tree Walk. At right: GIN’s Dr Emma Rooksby, UOW Environmental Officer Alison Scobie, UOW Botanist Patsy Nagle, and planter of local native trees on campus in the 70s, Leon Fuller. Photos: Kathryn Morgan

Alison thanked Leon Fuller, author of Wollongong’s Native Trees, for his vision and planting of the campus in the 1970s – a time when putting natives on a university campus was a radical move. Leon had relished his opportunity to plant endemic species. Today, those trees stand in their maturity, and Leon says it is now about creating a place where “trees are of a big enough scale that one gets the feeling of being in the landscape, not looking at it from outside”.

Alison also acknowledged Dr Anthony McKnight for his “kindness and patience in breaking down Western ways of doing things”. She hopes the renewed Tree Walk inspires people to take more walks – not only as recreation, but as care.

Aunty May Button’s Welcome to Country invited us to pay attention to what the trees teach us. Anthony, an Awabakal, Gumaroi and Yuin Cultural Man, elaborated on this invitation and, as we stood gathered in the rare shade, just outside the reach of the scorching sun, their message settled into our bodies as much as our ears.

“We won’t just learn from the signs,” he said, “but from the trees themselves, who are our teachers, our providers.” He gestured to the smooth white bark of one Eucalypt and the shaggy brown bark of that beside it. “Like us, trees live in families, with their bubs and their Aunties and Uncles and Grandparents. Would you cut down your Grandmother? How can we, as humans, give back?”

He pointed east, towards the distant Mt Ousley Interchange with its scar of recently cleared mature eucalypts. “I’m not saying stop infrastructure, I’m saying, how do we rethink and do things with Aboriginal knowledges and science coming together. Think with the birds, insects, possums and owls. We need to move from science that claims to be purely objective to science with a bit of spirit.”

UOW horticulture and fauna expert Anthony Wardle has been landscaping the campus for 32 years. He says the Tree Walk is not just a pleasant path but “an educational tool for uni students, school students, visitors, staff and locals.” There’s already “a positive buzz and lots of enquiries,” and a desire to see the walk expanded to include more trees.

He reminded everyone that trees visible now were once small. Leon chimed in: “Working with trees is full of surprises – you never really know what they’re going to do, and that’s the beauty of it.”

Collaboration rooted in Country

Former student and now media staffer Kassi Klower said the new signage creates “deeper engagement” – a way of pausing long enough to notice the textures, sounds, and the other critters living in the canopy, and she is excited for students to engage with this on their campus.

The revitalised walk is not only an interpretive project but a collaboration across scientific, Indigenous, horticultural and educational knowledge systems. It includes digital QR-coded signs linking to ecological information, campus environmental histories, and Indigenous perspectives. It is fully accessible and intentionally short and easy to follow – a few hundred metres threading through the campus core.

Behind the scenes, dozens of people contributed: digging 56 holes, protecting root systems, crafting precise wording, selecting historically significant trees, and ensuring that culturally sensitive knowledge was only shared with permission. Engineering students helped fabricate the signs; botanists and ecologists refined the language; Indigenous experts ensured the walk speaks respectfully to Country.

The Tree Walk reflects a shift that’s happening beyond the UOW campus – a growing understanding that trees are climate regulators, archives of place, habitat, and partners in imagining a future where learning is relational, situated and slow.

This year’s savage restructuring across the university sector – more than 3,700 jobs lost nationally, and up to 200 roles cut at UOW – shows how deeply neoliberal austerity has gutted higher education. The Tree Walk moves against that tide, offering a model of what public universities can be: collaborative, ethical, ecological, and accountable to Place.

The launch was held in the shade of a Moreton Bay fig. Photos: Michael Gray

The launch began and ended in the company of trees, with people gathering under branches talking, listening and learning together. The new Tree Walk invites the community to follow those paths, to sit with the trees, to recognise the gifts they give, and to consider how we might give back.

In Alison's words, it is an invitation “to inspire people to take more tree walks”.

And, as Anthony reminded us, to practice learning from the trees as Country. “You don't have to be Aboriginal to care for Country. Caring for Country is everyone’s responsibility.”

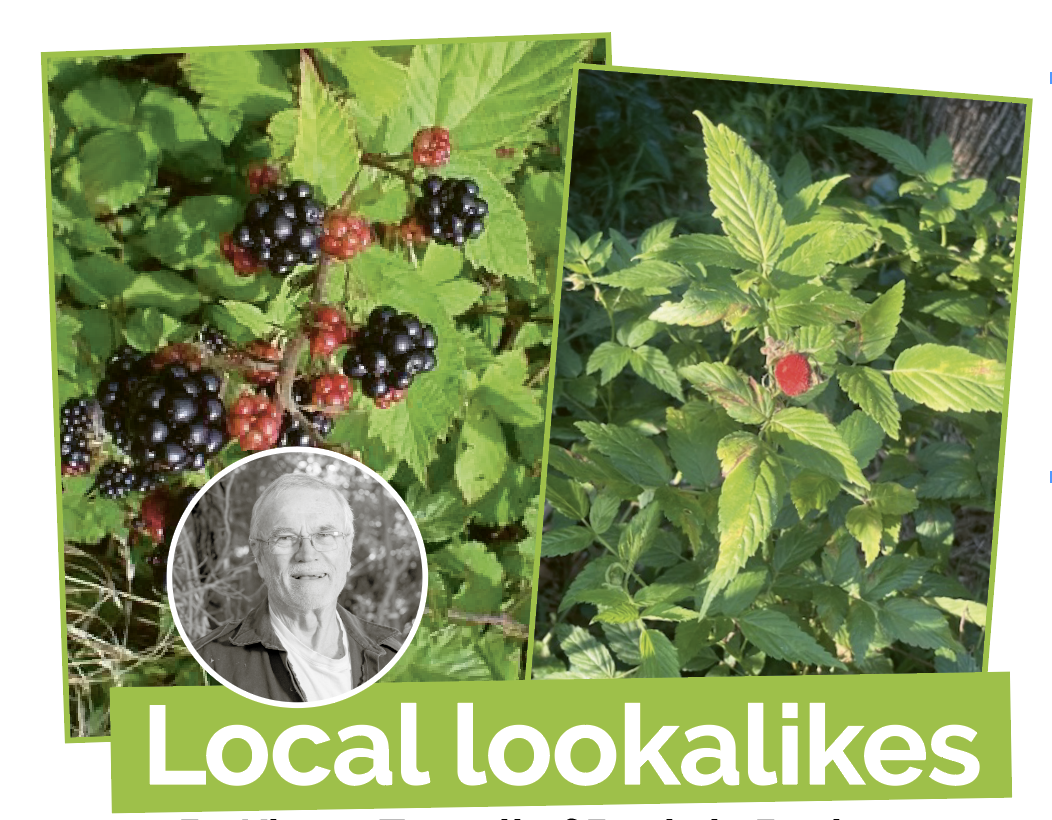

Anthony Wardle talks about tree selection and signage design on the walk. Right: a sign designed for Jackwood. Photos: Kathryn Morgan

UOW’s Tree Walk as green infrastructure precedent

As Australia faces a climate and biodiversity loss emergency (1), universities and the design professions are searching for examples of how the built environment can support ecological and cultural resilience. The revitalised Tree Walk offers a compelling and low-fi precedent.

The research of Dr Danièle Hromek has become a key reference for architects, planners and landscape architects. The Budawang Yuin spatial designer describes Country as alive, interconnected, and relational, not a resource but a relative. Designing with Country, she says, is an ethic that asks designers to slow down, listen deeply, and recognise that Country itself holds knowledge about how to live well in a place. (2)

Another influential theorist is Professor Margo Neale, who explains: “Country has Dreaming. Country is Dreaming. It is this oneness of all things that explains how and why Aboriginal knowledges belong to an integrated system of learning.” (3)

Such a conception of Country is embodied in the collaboration at UOW, and many of Anthony's explanations parallel the design principles articulated by Aboriginal spatial design theorists that underpin discourse in the profession around reconciliation, biodiversity and Indigenous knowledges. (4)

Walking around the grounds of UOW, the ethics of relationality stand out through the evident care and trust in plants themselves in the landscape. You can see this in the way huge trees are allowed to bend and hug one another, and tower beside the buildings, and you can see it in the shimmering ponds and creeks that the landscape team have listened to and tended across the campus. You could see it at the launch of the new signs, where all the makers gathered and chatted as collaborators and community.

As Alison noted, the project succeeded because “no one could have done it on their own” – it was collaborative and grounded in relationships.

Dozens of people contributed to the revitalised walk. Photos: Michael Gray

Across Australia, institutions are beginning to understand landscapes as living infrastructure. Anthony urged us to think not only of what trees do for us. Indeed, we need to be wary of the language of “ecological services”. Indigenous-led, Country-led design (the latter requiring the former) presents a counter to anthropocentric framing of ecology, rejecting the separation of culture and nature, and instead works through the inseparability of biodiversity and cultural continuity.

Comparable initiatives include Monash University’s Indigenous-led greening strategies, the University of Melbourne’s New Student Precinct designed around biodiversity and cultural practice, and the Australian National University’s campus ecology renewal. UOW’s campus and the Tree Walk offer something unique to those other examples: a 50-year proof-of-concept demonstrating what long-term ecological care can be.

Leon's insistence on planting Illawarra natives and big trees – lots of them, and close to buildings, means that today the campus is an urban forest complete with cooling, water retention, habitat, and stabilised soils. As Anthony Wardle put it, “The little things you do now become big things in the future."

What might this mean more broadly? It suggests that campuses, hospitals, schools, civic precincts, and infrastructure corridors can all become biodiversity nodes, cooling zones, cultural learning environments, and community refugia. It suggests that infrastructure can be regenerative, and the result is beautiful. It shows that designing with Country can create places where ecological processes, cultural knowledge, and human communities sustain one another.

In a year when Australian universities have been pared back by austerity, the revitalised Tree Walk is an oasis – a glimpse of what our institutions could prioritise if they chose care. It shows how educational landscapes can become places of reciprocity and long-range pluralistic thinking that commits to the crucial work of uncolonising education.

If Australia is to design its way through the climate crisis, we need universities brave enough to follow the lead of projects like this one.

References

- The Australian Institute of Landscape Architects’ 2019 Climate and Biodiversity Loss Emergency declaration positions landscape architecture as a frontline profession in responding to ecological collapse. It calls for Biodiversity Positive Design — approaches that restore ecosystems, integrate more-than-human relationships, and embed ecological thinking into all planning and development. This shift reframes landscape architecture not as embellishment, but as essential climate and biodiversity infrastructure.

- Hromek, D. (2020). Designing with Country: Discussion paper. Government Architect NSW & Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience.

- Neale, M. and Kelly, L. (2020) First Knowledges Songlines: The Power and Promise. Thames & Hudson

- Australian Institute of Landscape Architects. (2023). Biodiversity Positive Design Guide: AILA Position Statement.